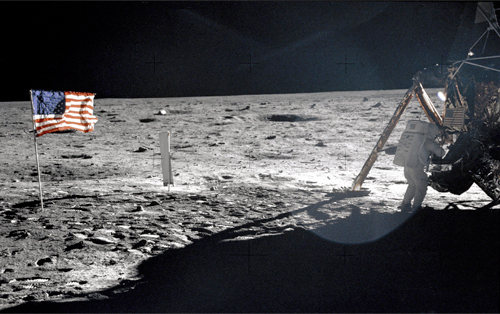

Photo courtesy of NASA

Recently I wrote about a new education innovation initiative being supported by some members of Congress. The initiative is based on the successful Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, which has been running in 11 federal agencies for decades. Each agency running SBIR sets aside a tiny percentage of its budget to award grants to small companies working to develop and evaluate new technologies. SBIR has received positive reviews from both the Government Accountability Office and the National Academy of Sciences.

I also recently wrote about Congress’ efforts to reauthorize the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). The Senate bipartisan compromise bill released last week by Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tennessee) and Patty Murray (D-Washington) was marked up in the Senate HELP Committee this week. On the second day of a three-day markup, Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colorado), with the support of Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), offered the new education innovation initiative as an amendment to ESEA. The amendment was passed by the Committee (with a block of other amendments) by voice vote, which means that it was considered noncontroversial. (The final bill passed the Committee unanimously this afternoon.)

While the passage of this amendment is only a small step for Washington in the greater marathon that is ESEA, it represents a giant leap for students nationwide.

First, let’s look at what the amendment does. It adds a section on “Education Innovation and Research” to the bill. This would provide grants for “the development, implementation, replication, or scaling and rigorous testing of entrepreneurial, evidence-based, field-initiated innovation to improve student achievement and attainment for high-need students.” It requires that at least 25 percent of the funds be used for students in rural areas. Grants may be provided to states and school districts as well as nonprofits, small businesses, charter management organizations, educational service agencies, or institutions of higher education working in partnership with a state or school district. Grantees can apply at any stage, and grant amounts will be based on the level of previous success and evidence of effectiveness in achieving desired educational outcomes. The amendment drew a broad coalition of support, and a letter with over 140 signatories was sent to the senators in advance of the markup to bolster support for the amendment at the markup.

Now let’s turn to what this amendment means politically and policy-wise, and what it will mean in the long run for communities and children across the country.

At one of the most divisive political moments in our nation’s history, in a piece of legislation that itself is controversial and has failed to be reauthorized despite numerous attempts over the past six years, a bipartisan amendment providing for education innovation and research sailed through a Senate committee. Politically, its inclusion in the chairman’s bill as it moves to the Senate floor means an extremely strong likelihood that it will withstand the floor process (should there be one) and make it into the final Senate bill. Even if ESEA fails to get reauthorized this Congress, the fact that this provision is now in the chairman’s bill sets an important precedent for inclusion in future attempts to reauthorize ESEA.

Policy-wise, this kind of bipartisan embrace of innovation and research in the realm of education represents a new era.

Congress and government in general is increasingly demanding evidence of effectiveness for education programs, a change that has enormous potential for improving programs for children.

The Bennet-Hatch amendment continues and advances the movement toward the use of evidence as a guide to policy and practice in education. There is still a lot to do even if this amendment becomes law, but the very fact that such a thing could happen is an indication that the ideas of evidence-based reform are no longer from the moon.