Recently I gave a series of speeches in China, organized by the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Nanjing Normal University. I had many wonderful and informative experiences, but one evening stood out.

Recently I gave a series of speeches in China, organized by the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Nanjing Normal University. I had many wonderful and informative experiences, but one evening stood out.

I was in Nanjing, the ancient capital, and it was celebrating the weeks after the Chinese New Year. The center of the celebration was the Temple of Confucius. In and around it were lighted displays exhorting Chinese youth to excel on their exams. Children stood in front of these displays to have their pictures taken next to characters saying “first in class,” never second. A woman with a microphone recited blessings and hopes that students would do well on exams. After each one, students hit a huge drum with a long stick, as an indication of accepting the blessing. Inside the temple were thousands of small silk messages, bright red, expressing the wishes of parents and students that students will do well on their exams. Chinese friends explained what was going on, and told me how pervasive this spirit was. Children all know a saying to the effect that the path to riches and a beautiful wife was through books. I heard that perhaps 70% of urban Chinese students go to after-school cram schools to ensure their performance on exams.

The reason Chinese parents and students take test scores so seriously is obvious in every aspect of Chines culture. On an earlier trip to China I toured a beautiful house, from hundreds of years ago, in a big city. The only purpose of the house was to provide a place for young men of a large clan to stay while they prepared for their exams, which determined their place in the Confucian hierarchy.

As everyone knows, Chinese students do, in fact, do very well on their exams. I would note that these data come in particular from urban Eastern China, such as Shanghai. I’d heard about but did not fully understand policies that contribute to these outcomes. In all big cities in China, students can only attend schools in their city neighborhoods, where the best schools in the country are, if they were born there or own apartments. In a country where a small apartment in a big city can easily cost a half million dollars (U.S.), this is no small selection factor. If parents work in the city but do not own an apartment, their children may have to remain in the village or small city they came from, living with grandparents and attending non-elite schools. Chinese cities are growing so fast that the majority of their inhabitants come from the rest of China. This matters because admirers of Chinese education often cite the amazing statistics from the rich and growing Eastern Chinese cities, not the whole country. It’s as though the U.S. only reported test scores on international comparisons from suburbs in the Northeastern states from Maryland to New England, the wealthiest and highest-achieving part of our country.

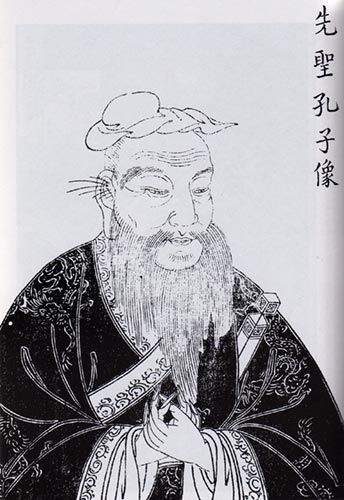

I do not want to detract in any way from the educational achievements of the Chinese, but just to put it in context. First, the Chinese themselves have doubts about test scores as the only important indicators, and admire Western education for its broader focus. But just sticking to test scores, China and other Confucian cultures such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore have been creating a culture valuing test scores since Confucius, about 2500 years ago. It would be a central focus of Chinese culture even if PISA and TIMSS did not exist to show it off to the world.

My only point is that when American or European observers hold up East Asian achievements as a goal to aspire to, these achievements do not exist in a cultural vacuum. Other countries can potentially achieve what China has achieved, in terms of test scores and other indicators, but they cannot achieve it in the same way. Western culture is just not going to spend the next 2500 years raising its children the way the Chinese do. What we can do, however, is to use our own strengths, in research, development, and dissemination, to progressively enhance educational outcomes. The Chinese can and will do this, too; that’s what I was doing traveling around China speaking about evidence-based reform. We need not be in competition with any nation or society, as expanding educational opportunity and success throughout the world is in the interests of everyone on Earth. But engaging in fantasies about how we can move ahead by emulating parts of Chinese culture that they have been refining since Confucius is not sensible.

Precisely because of their deep respect for scholarship and learning and their eagerness to continue to improve their educational achievements, the Chinese are ideal collaborators in the worldwide movement toward evidence-based reform in education. Colleagues at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Nanjing Normal University are launching Chinese-language and Asian-focused versions of our newsletter on evidence in education, Best Evidence in Brief (BEiB). We and our U.K. colleagues have been distributing BEIB for several years. We welcome the opportunity to share ideas and resources with our Chinese colleagues to enrich the evidence base for education for children everywhere.

This blog was developed with support from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Foundation.